Editor’s Note: At the time of publication, a bill with slightly different parameters than those analyzed in this piece was close to becoming law — we will update the findings in this analysis once all relevant details are clear. Our aim in publishing now was to give an early sense of how the financial situation for the most-impacted households changes depending on various assistance scenarios. We also wanted to illustrate the very tenuous situation some of these households are facing in the absence of any assistance.

Rent affordability has been a growing concern for many American households. Add in the loss of income and/or lack of protections like paid sick leave for millions of these renters in the wake of the unfolding U.S. coronavirus outbreak, and many that were already vulnerable to economic shocks may become even more at-risk of failing to secure adequate housing.

Almost all workers have been impacted to some degree by ongoing business closures and social distancing requirements as the disease has spread, but among the most susceptible to the economic impacts of temporary business closures and/or social distancing include food-service and retail workers. Zillow estimated how missing work for a period of time and/or not receiving paid benefits while out of work may impact rent affordability and household budgets for these workers.

Zillow analyzed the impacts on rent affordability for households working in Retail Trade and Arts, Entertainment, Recreation, Accommodations, and Food Services according to the 2018 American Community Survey, including jobs like waiters or store clerks. We also ran the analysis on households split into three earning-structure groups, based on the number of workers and share of earnings coming from the industries we examined.

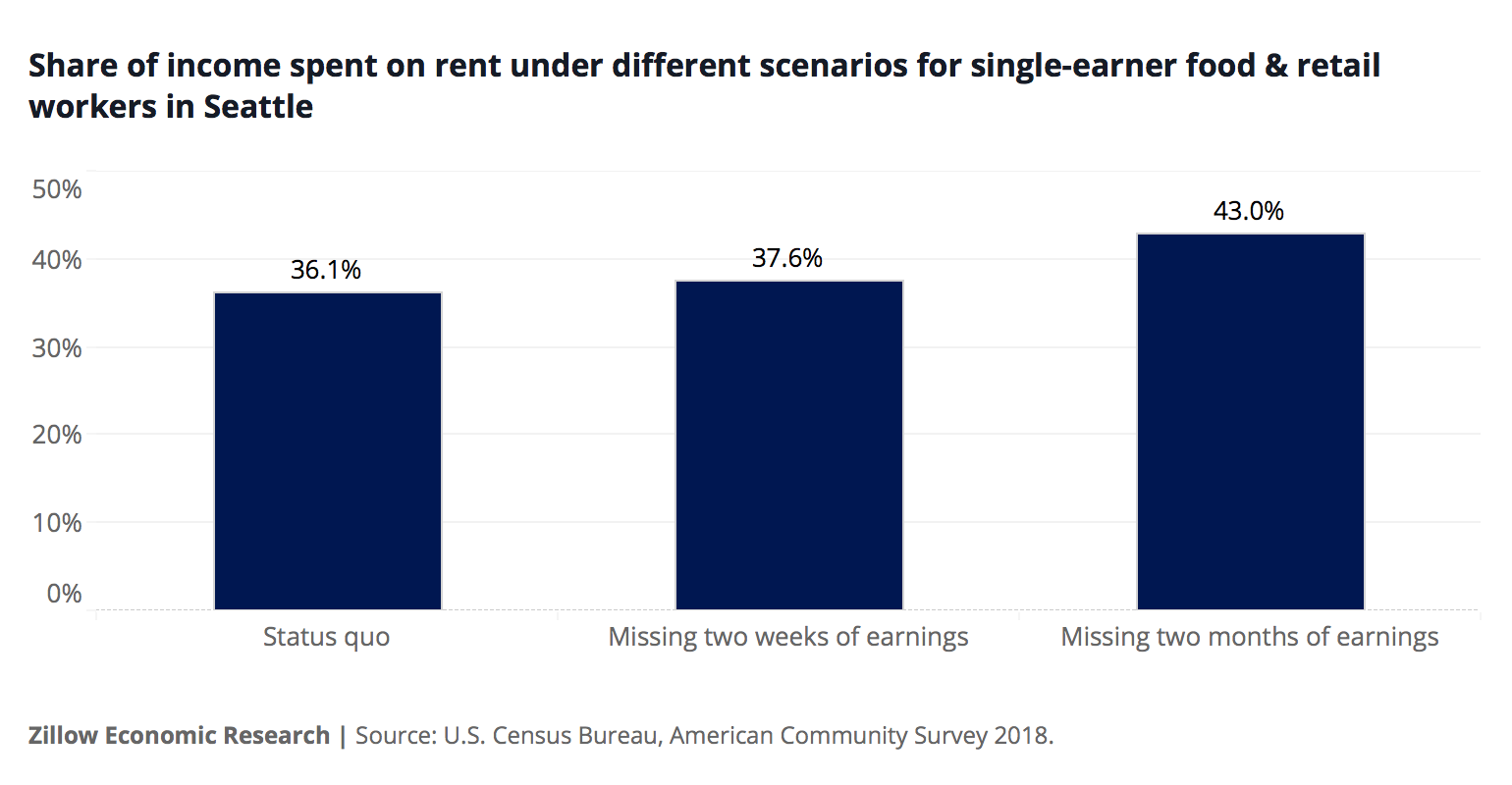

Assuming two weeks off without pay, single-earners working in these industries in the Seattle metro – among the markets hit earliest by the crisis – should expect to spend more of their limited income on rent (the median share of annual income spent on rent rises to 38%, compared to 36% without an income loss). These same workers should also expect to take a 5.5% ($1,300) cut to their annual household budgets after rent is paid (assuming lost hours couldn't be made up later).

In more normal times, a mildly ill worker might be expected to come to work anyway and/or to only miss a few days of work before returning. But the intense need during this particular outbreak to keep potentially ill employees at home for several weeks – or longer — despite a loss of earnings has helped reignite discussion on Capitol Hill regarding the availability of paid leave benefits for workers. Because the longer they're out of work without pay, obviously, the more financial pain is inflicted.

In Seattle, if those same workers in one of the affected food and retail industries are forced out of work for 2 months without compensation, they would be forced to pay 43% of their remaining annual income on rent, and would take an almost 25% hit ($5,600) hit to their remaining annual non-housing budget.

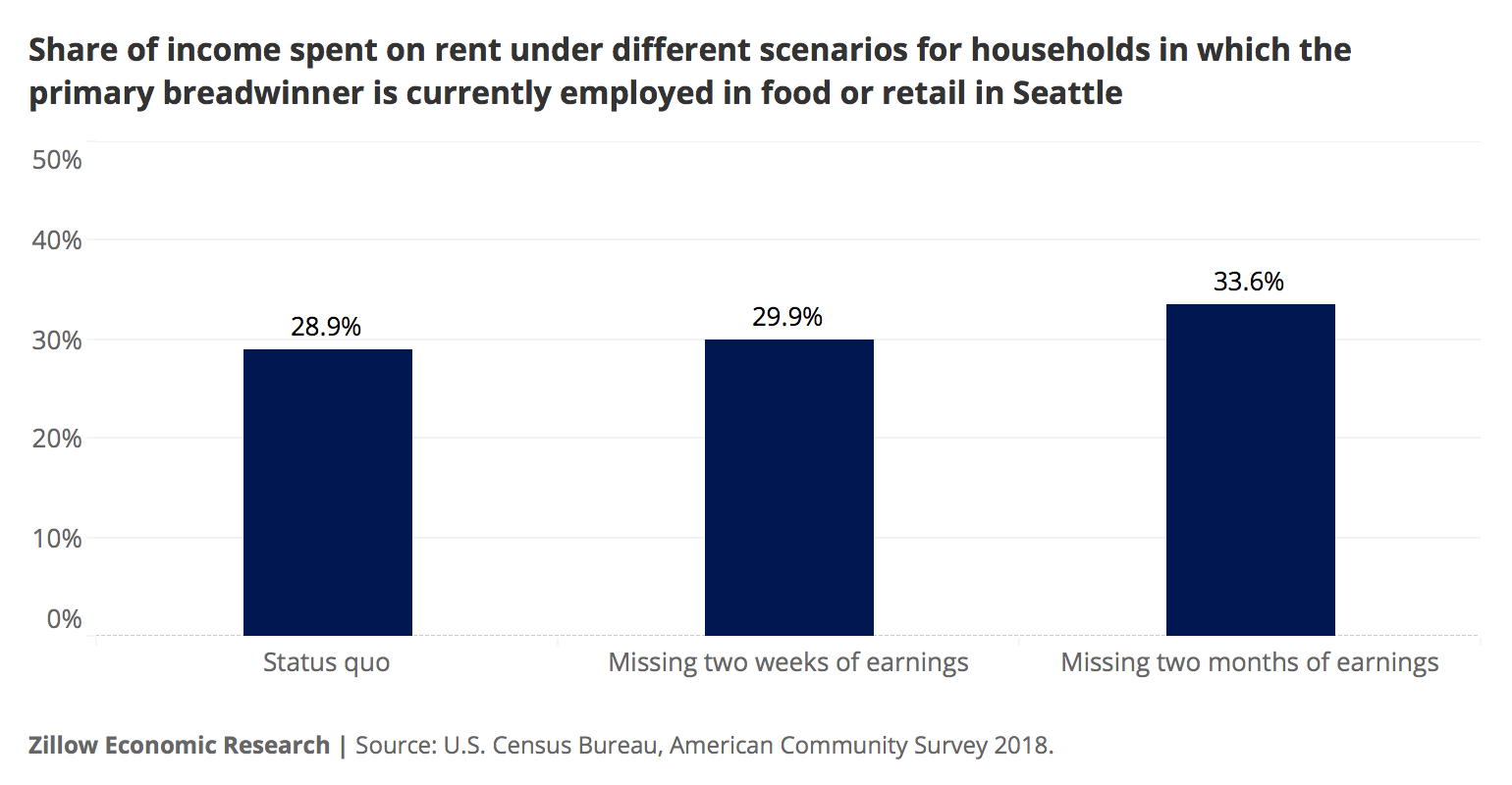

Multi-earner households working in these sectors may have a bit more of a cushion, but are by no means immune to the pain of extended income loss. In particular, households in which the primary breadwinner works in these industries, with or without additional earners, are among the most acutely impacted by income loss. In the Seattle-area, 2 months without pay for these households could reduce the median annual budget – after rent – by $8,000, or almost 22%. All of this assumes, however, that rent bills can be paid in time to avoid eviction despite a loss of income. This can be very challenging for households that may have been living paycheck-to-paycheck before emergency eviction protections were put in place.

Thankfully, policymakers aren't blind to the risks, and a number of plans have been proposed to alleviate the pain somewhat, including:

- A one-time $1,000 check per adult

- A $1,200 payment per adult and $500 per child

- A $1,500 payment per person in a household

- Payments of $2,000 per adult and $1,000 per child for each month of the crisis.

We also measured how these potential subsidy scenarios could impact the median rent burden among various households with workers in the food and retail industries missing 2 months pay.

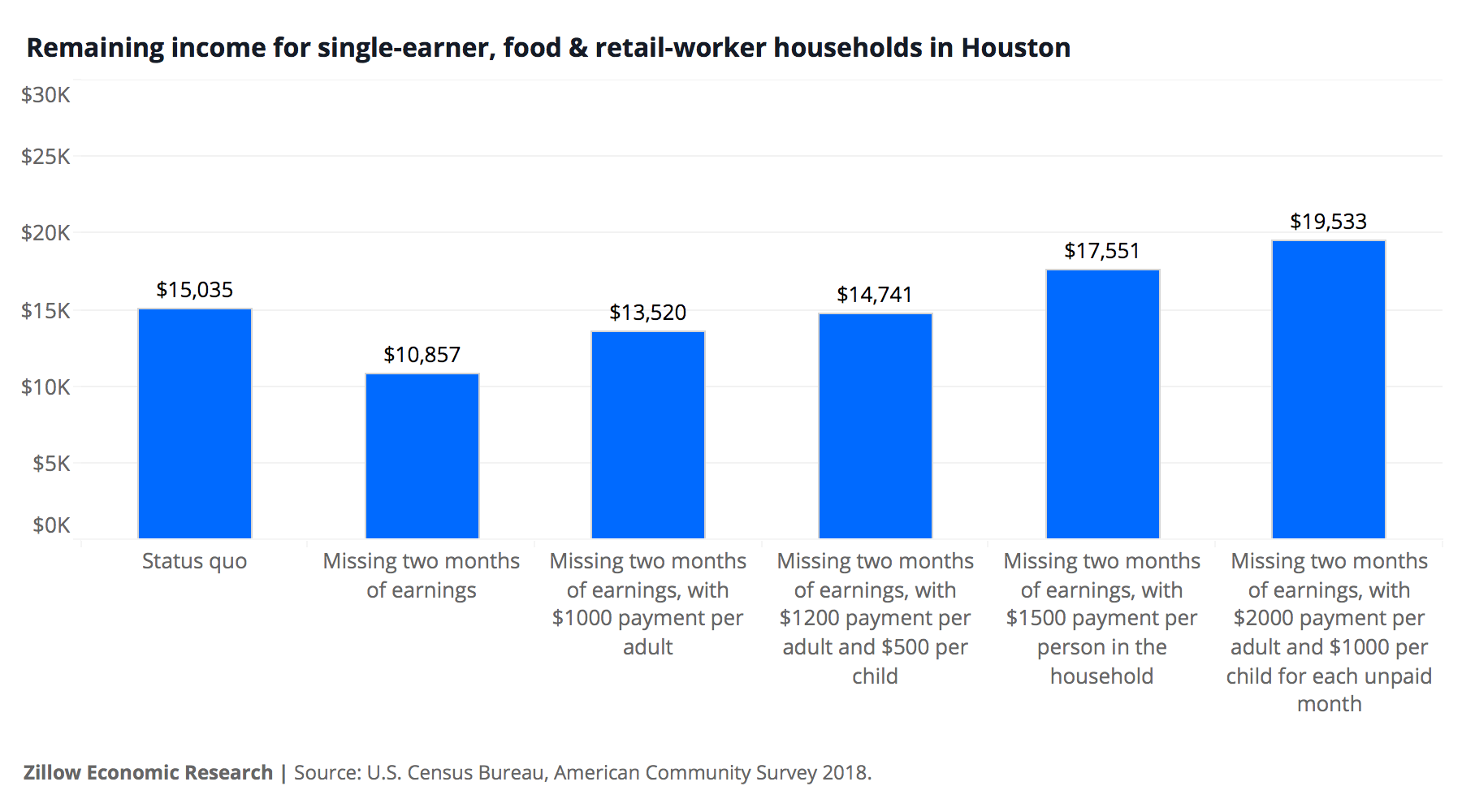

Single-earners in the Houston metro who lose their income for 2 months, but receive a $1,000 check per adult in the home, could expect to see their rent affordability improve somewhat, from spending 46% of their annual income on rent before the cash assistance, to 41% after. If the same Houston-area households received $1,200 per adult and $500 per child, the median rent burden would fall to 39%. Receiving $1,500 per every member of the household (including children) lowers the median rent burden to 36%. Finally, a $2,000 cash transfer per adult and $1,000 per child for each month without income would drop the median rent burden to 28%, and raise the median annual after-rent budget (assuming two lost months of income) from just under $10,900 to more than $19,500 after the assistance.

These are just a handful of examples of impacted workers from a small sample of markets. Use the tool below to see how rent affordability and household budgets change under a number of scenarios for food-service and retail workers in dozens of large markets nationwide.

These are just a handful of examples of impacted workers from a small sample of markets. Use the tool below to see how rent affordability and household budgets change under a number of scenarios for food-service and retail workers in dozens of large markets nationwide.

Workers in these industries and other acutely affected households are well-represented in our communities, and the impacts of lost income and higher rent burdens could be vast. In some markets, including Las Vegas and Orlando, more than a quarter of the local workforce is employed in the Retail Trade and Arts, Entertainment, Recreation, Accommodations and/or Food Services industries. Clearly, help is desperately needed.

But the devil is in the details, and differences in these potential cash assistance programs vary by more than just the dollar amount the typical household could receive. In some earlier versions of some proposals, eligibility thresholds that require some minimum amount of taxable income could have left the most vulnerable households – those with lower incomes and/or higher rent burdens — with diminished assistance. Both Democratic and Republican leaders have recognized this as problematic, and continue to work to ensure cash assistance is directed to all experiencing the fallout of this crisis, especially those in the least stable financial position. This was addressed in later proposals. Higher-income households may have more of a cushion, but also aren't immune – especially those in which one or more earners are in food-service or retail, and other earners are in other industries. Some bills under discussion would phase out assistance for those earning above certain thresholds, and while we're continuing to model the impact of potentially smaller payments to these households for the purpose of this analysis no phase-outs based on income were assumed. Exact results may differ for higher earners based on phase out requirements within final bill texts.

Finally, one last, critical note: It's clear that the economic effects on renters in the most impacted industries from long-lasting loss of hours and/or lack of paid leave protections have the potential to be devastating. Help, in whatever form it takes, will be welcome. But the most important relief has little to do with legislative efforts, and everything to do with ongoing public health efforts centered around stopping the spread of the virus itself. Social distancing is hard. But without drastic measures now, we run the very real risk of prolonging the crisis later and preventing the "normal" economy from re-emerging, recovering, and putting these employees back to work – which will ultimately prove the best kind of help available.

Methodology

Zillow utilized 1-Year American Community Survey (ACS) data from 2018 to model how workers in Retail Trade and Arts, Entertainment, Recreation, Accommodations, and Food Services industries (as outlined by ACS) would be impacted by income shocks resulting from inability to work or loss of work in terms of rent burdens. We include all Retail Trade industries except for Electronic shopping and mail-order houses.

Zillow analyzed households in the top 35 metros in each of the three following categories:

- Single-earner households where the earner works in the affected industries

- Households with one currently employed person with valid personal income (nonzero, non-NA) that is >=95% of household income, working in the affected industries

- Multi-earner households where at least one adult works in the affected industries

- Of all household members with valid personal income, there is at least one currently employed in the affected industries

- Households where the "breadwinner" works in the affected industries

- One person in the household is currently employed in the affected industries, with a valid personal income that is >50% of household income

Income shock scenarios assume affected earners in each household work 50 weeks in a year, and rent burdens are smoothed over the year. Incomes and rent burdens under each scenario are calculated at the household level, and aggregated to the median household at the metro level. Rent burdens are defined as total household income, divided by monthly contract rent then multiplied by 12 to estimate the yearly contract rent. Shocks to income from the affected industries would be applied to the total personal income coming from the relevant earner, the remaining household income less that personal income is unchanged.

The post Two Months without Pay Pushes Food and Retail Workers to Spend 40% of their Annual Income on Rent appeared first on Zillow Research.

via Two Months without Pay Pushes Food and Retail Workers to Spend 40% of their Annual Income on Rent

No comments:

Post a Comment