- Latinx, Asian and black workers are disproportionately represented in the food, arts and service industries that have been affected by mass layoffs and furloughs.

- Non-white households in these industries were more cost-burdened than white households before any loss of wages, meaning they are potentially more vulnerable to experience housing insecurity after missing pay.

- Financial assistance from the CARES Act and unemployment insurance should plug gaps in income for those who qualify, at least temporarily.

While everyone's lives have been shaken by the coronavirus outbreak, the most devastating economic and public health outcomes have fallen along socioeconomic and increasingly racial lines.

Workers in industries on the front lines of job losses and furloughs — notably food and retail — are feeling an especially acute pinch as months without income leave them vulnerable to unsustainable living costs. Among the most troubling trends to emerge from this pandemic has been how the virus and disease itself has disproportionately impacted communities of color. And in addition to the public health disparities, the economic impacts of the coronavirus outbreak are also experienced very differently across racial lines.

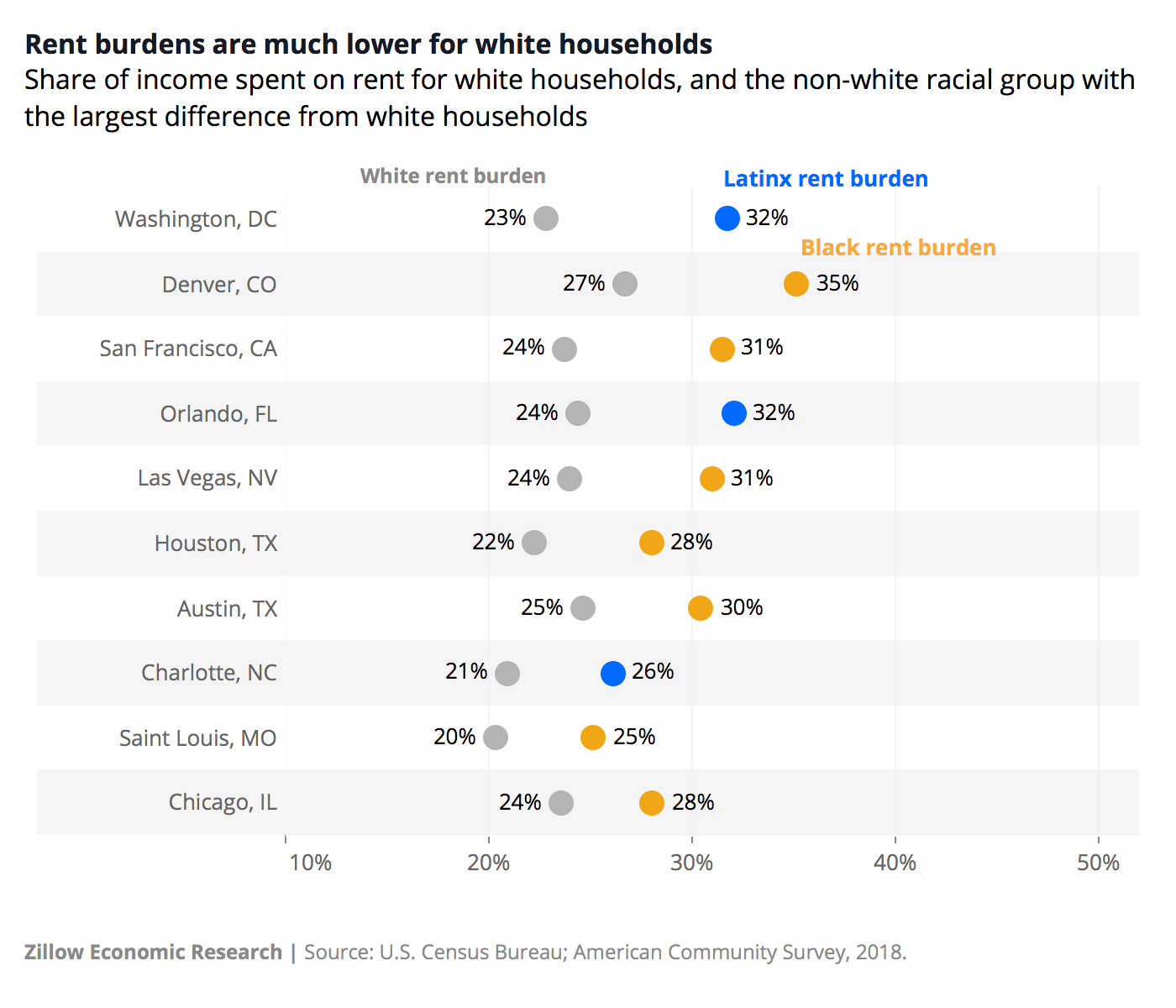

In virtually all the nation's largest metros, Latinx or Black renter households face larger rent burdens than other racial groups. The difference between white households and households of color is largest in Washington, D.C., where Latinx households pay almost a third of their income on rent (32%), compared to less than a quarter paid by white households (23%). Black and Latinx households already typically earn less than other groups, and when coupled with generally higher rent burdens that means non-white households generally have much less income left over after paying rent to cover other household expenses. White households in D.C. have almost twice as much income leftover compared to Latinx households – roughly $67,000 per year, compared to $36,000, respectively. In San Francisco, black households have just $22,350 per year leftover after paying rent, less than a third of what white households have left ($76,962), the largest such disparity among the nation's 35 largest metro areas.

Black and Latinx households already typically earn less than other groups, and when coupled with generally higher rent burdens that means non-white households generally have much less income left over after paying rent to cover other household expenses. White households in D.C. have almost twice as much income leftover compared to Latinx households – roughly $67,000 per year, compared to $36,000, respectively. In San Francisco, black households have just $22,350 per year leftover after paying rent, less than a third of what white households have left ($76,962), the largest such disparity among the nation's 35 largest metro areas.

So, households of color are already holding a weaker hand — and that's before considering that non-white populations are also disproportionately represented in jobs sensitive to the layoffs and furloughs common during this time. In March, the food and arts industries experienced a startling surge in unemployment. Compared to the previous 12 month average, 100% more workers in the food industry and 93% more workers in the arts industry filed for unemployment last month.

Nationally, a larger share of non-white racial groups' workforces are employed in the food and arts industries, particularly Latinxs. Among working Latinxs, 13% are employed in the food or arts industries. About 10% of both black and Asian employment is in these affected industries, compared to 8% of White workers. Las Vegas, a metro especially vulnerable to the impacts of coronavirus due to its reliance on leisure-bound industries, has the highest shares of non-white workers employed in food and arts. About a third of both Asian and Latinx workers in Las Vegas (33% and 32%, respectively) and a quarter of black workers (26%) work in Vegas' food and arts businesses, compared to just a fifth (21%) of local white workers.

Given their relatively larger exposure to layoffs and job losses in these vulnerable industries, non-white households also stand to face some of the biggest losses in income. And for lower-earning households already dedicating an uncomfortable share of their pay toward rent, monthslong shocks to their income could easily push them into housing insecurity.

We looked at households where the majority of household income came from either the food, arts or retail industries — industries not only adversely impacted by shelter-in-place orders, but also among those most unlikely to offer paid leave. In Chicago, where infection rates have been particularly devastating for the black population, black households relying on wages from these industries typically pay 30% of their income on rent — right at the top of recommended guidelines on how much to pay for housing — leaving $18,000 of their income left per year after rent. Losing two months of pay pushes the share of remaining income spent on rent to 35%, with $14,000 leftover for other expenses. For black households in Chicago, four months without pay puts their rent burden at 42%, with a scant $10,000 left for other living expenses for the year — or roughly $830 per month to cover food, gas, household bills and other essentials.

In this lens, the importance of the assistance provided by the CARES Act– which provides unemployment insurance at standard levels for up to 39 weeks, with an additional $600/week through July 31– and state-level unemployment insurance cannot be overstated. At two months without pay, but with the direct payments and unemployment benefits offered at the state and federal level, black households in Chicago could see their rent burdens fall to 26%, and to 23% with four months of unemployment.

The fact that rent burdens are lower with these benefits than if wages hadn't been lost at all underscores the undeniable fact that many households now at the front lines in "essential" services — working at grocery stores and pharmacies, keeping transit running — were already experiencing high rent burdens and affordable housing concerns. In fact, rent burdens across racial groups working in these industries are often quite similar when looking metro-by-metro. And for all racial groups in all metros, we find that losing four months of pay but getting the maximum possible unemployment and stimulus benefits leaves the median household working in these industries better off than before in terms of their rent burden.

Even so, this analysis of incomes and rent burdens under different assistance scenarios are also best-case assumptions. We assume a household can smooth their expenditures across a year — that a late stimulus check or unemployment insurance benefit won't mean they can't make rent or be able to buy food. And this is all predicated on the assumption that these workers will, in fact, actually receive these benefits — that they qualify and are able to dedicate substantial time and effort to get them in an environment where state unemployment agencies are overwhelmed by applications. Furthermore, while expanded unemployment benefits clearly represent a significant economic lifeline for those receiving them, there is no guarantee that four months of assistance will be enough to fully cover the full duration of lost income. It remains to be seen how quickly new jobs can be created and/or previous jobs resumed once the virus passes, and the employment prospects for these workers are by no means guaranteed to improve just because four months have passed on the calendar.

And finally, recent shocking unemployment figures — roughly 25 million Americans have applied for unemployment insurance benefits since mid-March — in all likelihood actually understate the true pain being felt. Many Americans who have experienced some disruption in their work may still not technically count as "unemployed." While 1.4 million Americans became unemployed between mid-February and mid-March, that number was virtually matched by those reporting labor market disruptions short of full unemployment but that also mean a loss in income — including shorter hours, fewer shifts and/or pay cuts. According to analysis of CPS data by Ernie Tedeschi, over that same time period, 1.2 million people said they wanted more hours, and another 1.2 million reported being employed but absent.

Notably, Latinxs experienced the largest rise in the rate of labor market disruptions compared to other racial groups.These marginally employed individuals may be struggling to pay their costs even more than their truly unemployed peers.

Methodology

- 1-Year American Community Survey (ACS) data from 2018 was used to determine rent burdens and incomes after rent. Latinx is equivalent to Census definitions of Hispanic, and can be any race. All other races (White, Black, Asian) only include non-Latinx persons. American Indian or Alaska Native and Other races (as coded by ACS) were not included in our analysis due to low sample sizes. Only races with at least 100 observations in a metro were included.

- Department of Labor ETA 203 was used for unemployment claims across races and industries.

- Zillow modeled how workers in Retail Trade and Arts, Entertainment, Recreation, Accommodations, and Food Services industries (as outlined by ACS) would be impacted by income shocks resulting from inability to work or loss of work in terms of rent burdens.

- We looked at households in which at least 50% of household income came from individual incomes in the above industries.

- Income shock scenarios assume affected earners in each household work 50 weeks in a year. Incomes and rent burdens under each scenario are calculated at the household level, and aggregated to the median household at the metro level.

- See our previous research for methodology on calculating CARES payments at the household level.

- For state unemployment, we assume individuals working in the affected industries receive their weekly wage multiplied by the state's replacement rate, for each unemployed week, up to the state's benefit maximum. For federal unemployment stemming from the CARES Act, we assume individuals working in the affected industries receive their $600 per unemployed week.

The post Coronavirus Layoffs Have Bigger Impacts on Housing Security for Black, Latinx and Asian Households appeared first on Zillow Research.

via Coronavirus Layoffs Have Bigger Impacts on Housing Security for Black, Latinx and Asian Households

No comments:

Post a Comment